A tough spring

This week we look at jobs and pay. Big policy changes—to taxation, and to minimum wages—were put in place in April. It could be a tough spring for young workers.

What are the most important measures in an economy? Is it imports and exports? With all the recent trade talk—including our newsletters on Liberation Day and Britain’s Steel crisis—you might think so. Perhaps it is investment or R&D spending? These things certainly matter, but they don’t matter the most. The top spot is reserved for labour market measures—jobs and pay.

Employment and wage data matter so much for a host of reasons. To take just one, they have a tight link to consumption (aka shopping). Household consumption makes up 60% of GDP, dwarfing exports, at 30%, and investment at 17%. So, if you want to understand whether an economy is likely to grow or shrink, look to the world of work.

Big changes are taking place in British workplaces. First, to how jobs are taxed. Last summer’s budget set out a rise in the National Insurance Contribution (NIC) rate paid by employers (from 13.8% to 15%). The threshold at which employers start paying was cut from £9,100 to £5,000. This was forecast to raise an additional £25 billion a year in tax revenue.

Second, higher minimum wages. The minimum rate—the National Living Wage—for those 21 or over is now £12.21, a 7% increase. Younger workers have seen a bigger rise: their rate went up 16% (around 13%, after accounting for inflation). An 18-year-old is now guaranteed at least £10 per hour in Britain.

A third change—this time coming from Washington, instead of Whitehall—is tariffs. Stories from individual firms already suggest trade uncertainty is taking a toll. Last month, for example, Lotus cited tariffs and volatile markets in explaining mass redundancies. Higher tax, higher pay, higher uncertainty—it adds up to a tricky mix—how robust is Britain?

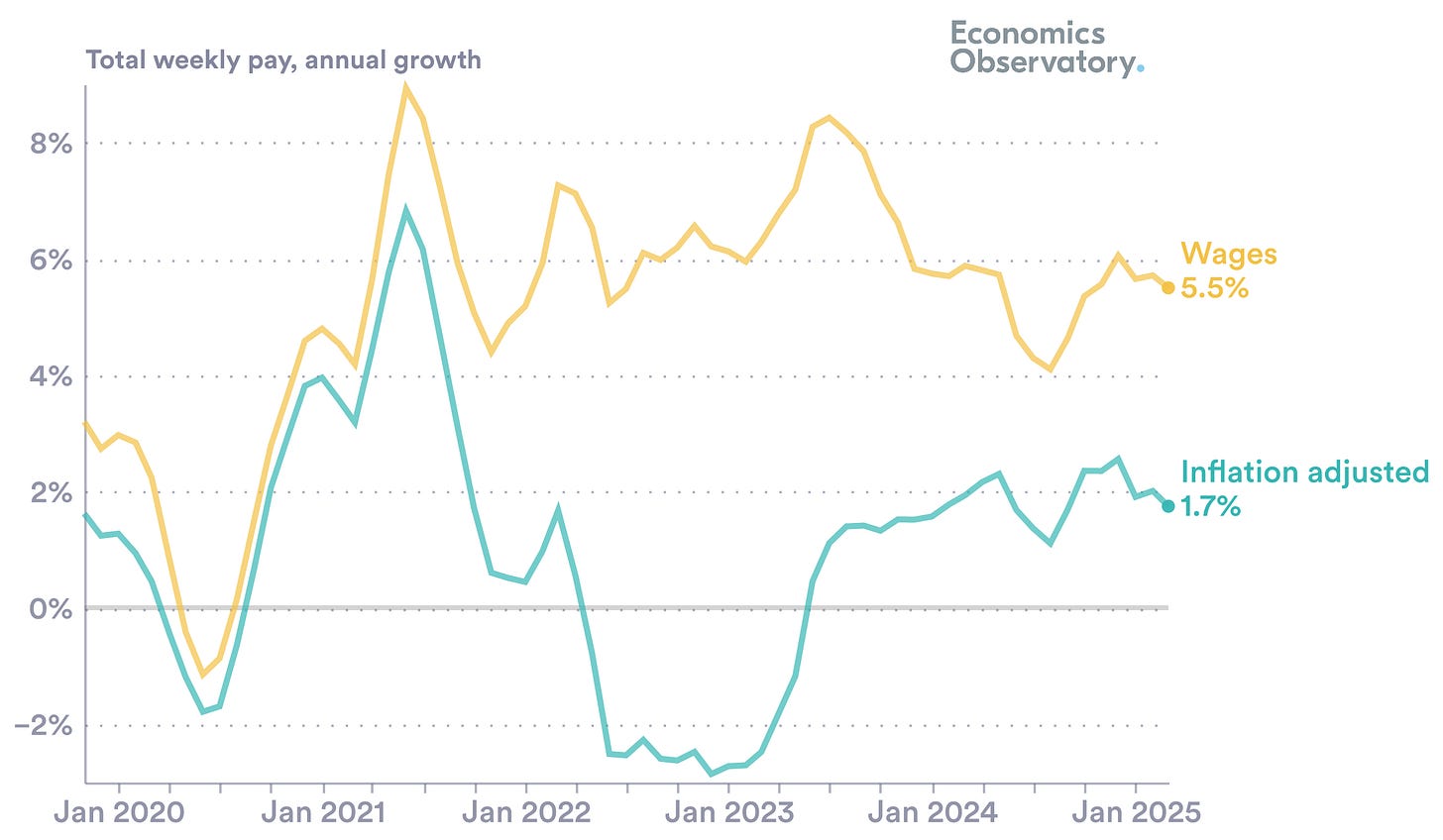

On wages, there is positive news. The latest pay recorded in official ONS data released this week was up more than 5% over the year. This rise is faster than price increases: inflation-adjusted wage growth is almost 2%. This was not the case in 2022 and 2023 (see Chart 1 below) where inflation more than offset wage gains. On average, living standards are rising.

Chart 1: Pay is rising

Source: ONS

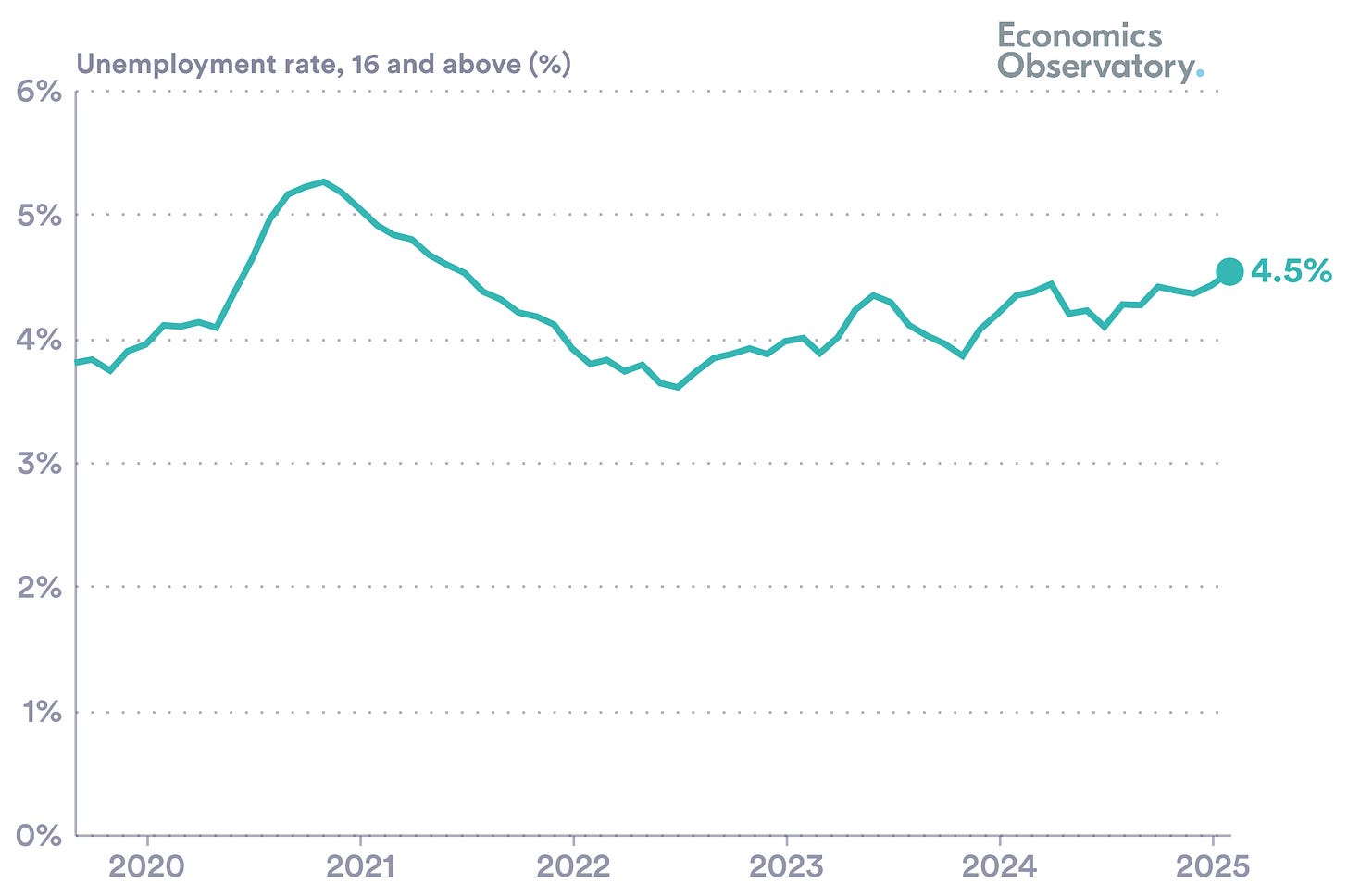

Job numbers are more mediocre. Unemployment has been creeping up for a couple of years and is now 4.5% (Chart 2). While we are doing better than Italy, Canada and France, who all have unemployment over 5%, we lag the US, Germany and Japan. In terms of the G7 countries, the UK is middle of the pack.

Chart 2: Unemployment is creeping up

Source: ONS

The bubbling concern is the cocktail of tax and mandatory wage rises. The logic runs as follows. National insurance payments add a wedge—the government’s slice—between what a firm must pay per hour, and what a worker receives. When NI rates go up one option is to cut pay to partly offset the tax. This would mean that both workers and firms would share the pain—both would absorb the tax rise. But if workers are on the minimum wage their pay cannot be cut. To trim its payroll, a firm would need to lose staff.

Analysing the data and the policy changes, Nye Cominetti and Gregory Thwaites at the Resolution Foundation predict that 80,000 jobs could be lost, concentrated among lower-wage workers. Many others, including the IFS, have set out similar concerns. The wage and tax changes only went live last month (on the 1st and 5th of April respectively) so it is a bit early to assess these predictions—what should we be tracking?

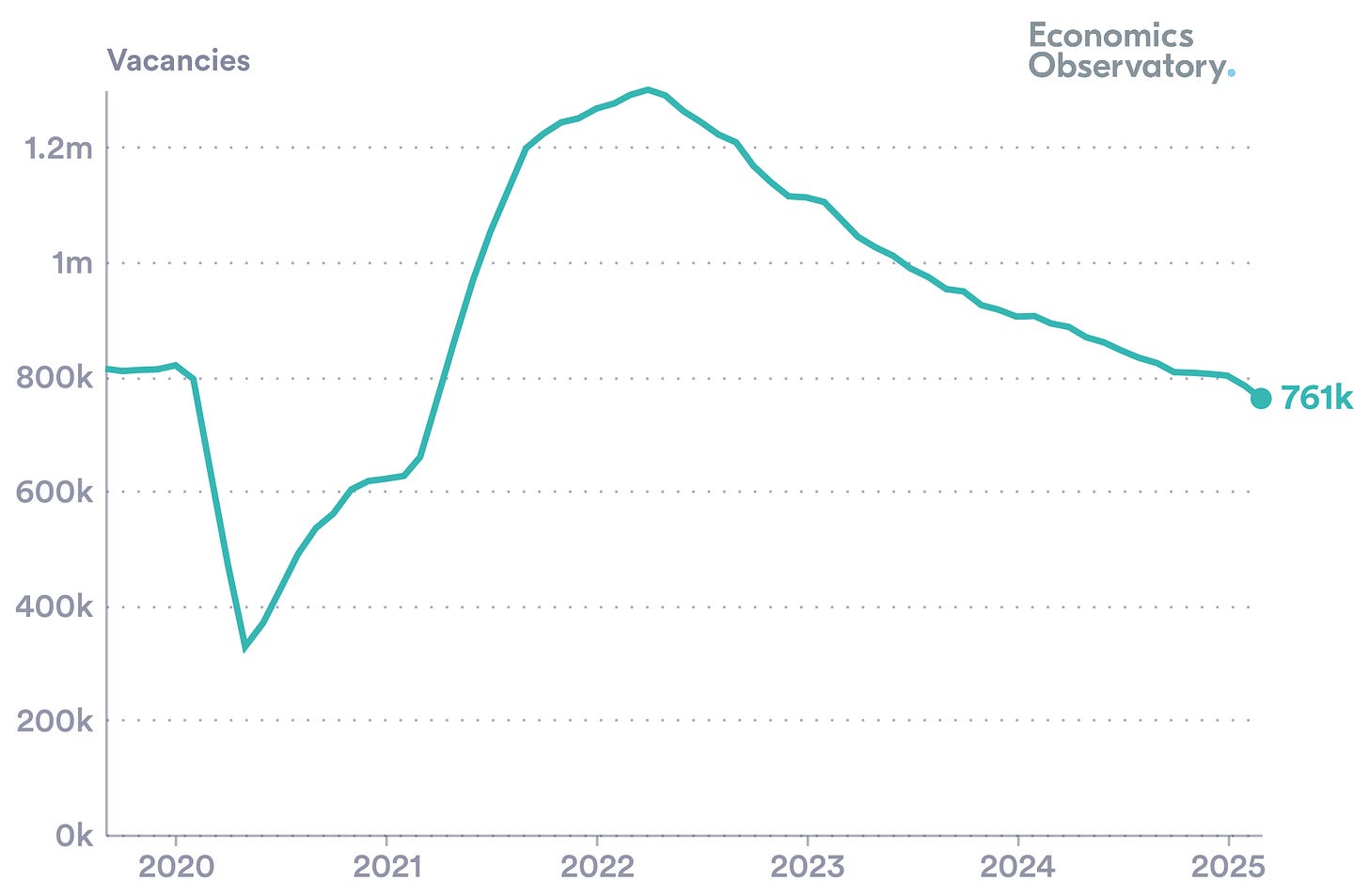

The number of vacancies provide one useful yardstick. Data for April are available and may capture some of the shifts in UK (and US) policy. There was a 3% monthly drop, the sharpest decline in the past two years (Chart 3). Monthly numbers can bounce around so this may be a blip, but it’s a blip worth monitoring.

Chart 3: Total vacancies

Source: ONS

The youth of today

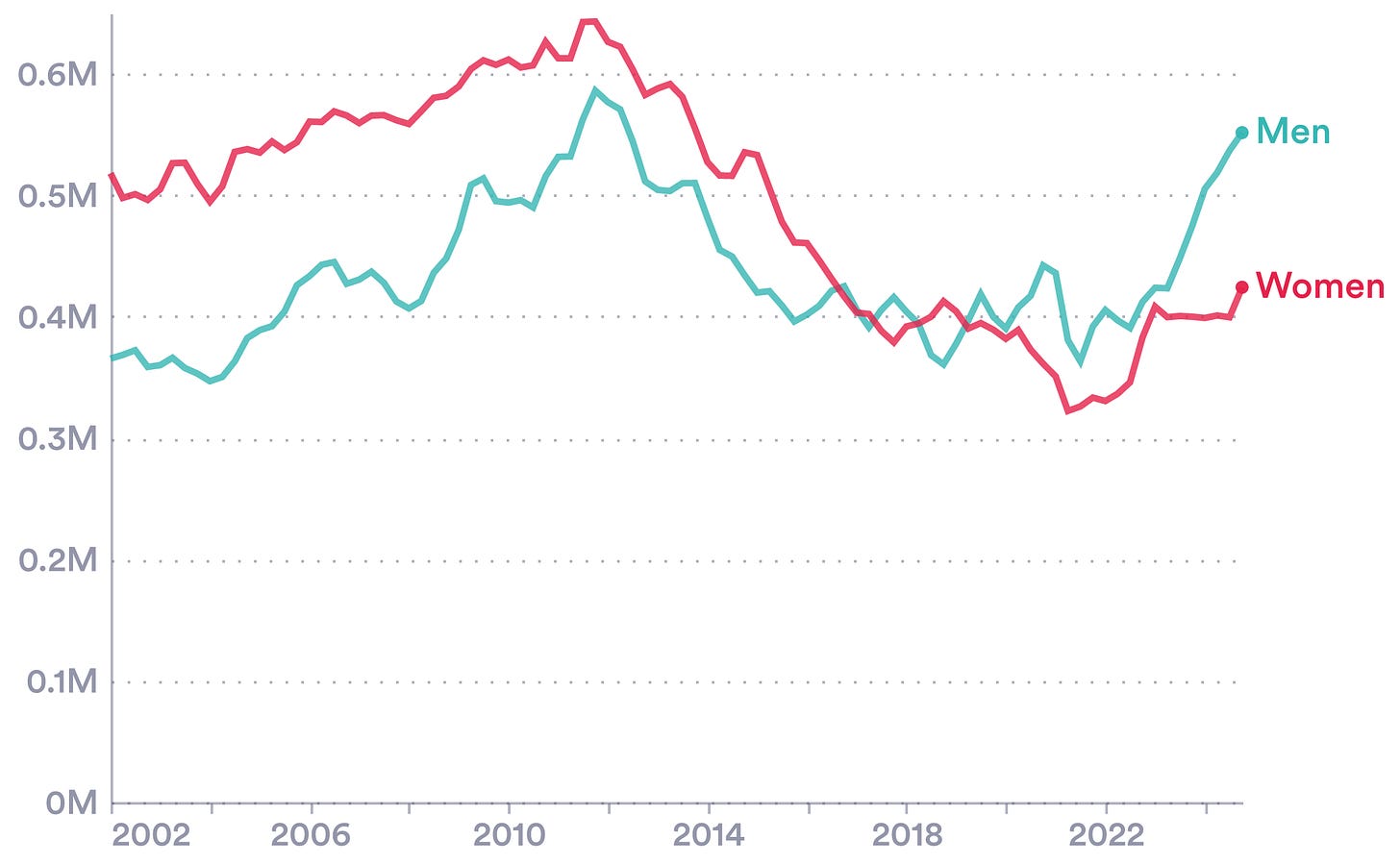

The most important group to track, as Britain shifts to a higher-tax, higher-pay economic model will be the young. In recent years the unemployment rates for the youngest Britons have been creeping up. The UK’s ‘NEET’ problem—young people not in education, employment, or training—is making a comeback (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Is UK’s NEET problem returning?

Source: ONS. Note: NEET, young people (aged 16 to 24 years) who are not in education, employment or training, by age and sex.

The recent economic shifts—tax, wages and uncertainty—will take the greatest toll in labour-intensive industries. Top of this list are hospitality and retail, precisely the sectors where young people get their first jobs. The IFS is concerned that young Briton will now face a tougher time getting onto the job ladder. And we know that young people in work are less secure: in redundancy processes they cost less to remove. The dangers seem stacked against the young.

In an ideal world, you’d load the risk elsewhere. Joblessness matters more for the young than those with experience. This is because young adults are prone to so-called ‘scarring’ effects–meaning that their lifetime job and pay opportunities can be irreparably damaged by a period of unemployment. It is too soon to call this a downturn for Britain’s young workforce, but these are datapoints UK policymakers should be watching closely.

REFERENCES

Impact of April’s policy reforms

Resolution Foundation. Minimum wage, maximum pressure? The impact of 2025’s minimum wage and employer NICs increases

House of Common Library. Impact of planned changes to employer National Insurance contributions on police forces

Labour market

Financial times. The minimum wage is now coming for white-collar work

Arindrajit Dube. Impacts of Minimum wages: review of the international evidence