Pastries, pints and price pressures

This week we look at prices, selecting two staples that are getting more expensive and which tell stories about Britain's economic divisions, and its changing high streets.

Prices made the headlines this week. Inflation jumped to 3.5%, rising more than economists had expected. In today’s letter we dive deep into the data.

The price surge was driven by utilities—regulated rises came into effect in April. There was a particularly dramatic increase for water, with the average household set to pay £603 per year, a rise of 26% (or around £12). Another big contribution, also set by regulators, came from transport which was largely due to the price of flights.

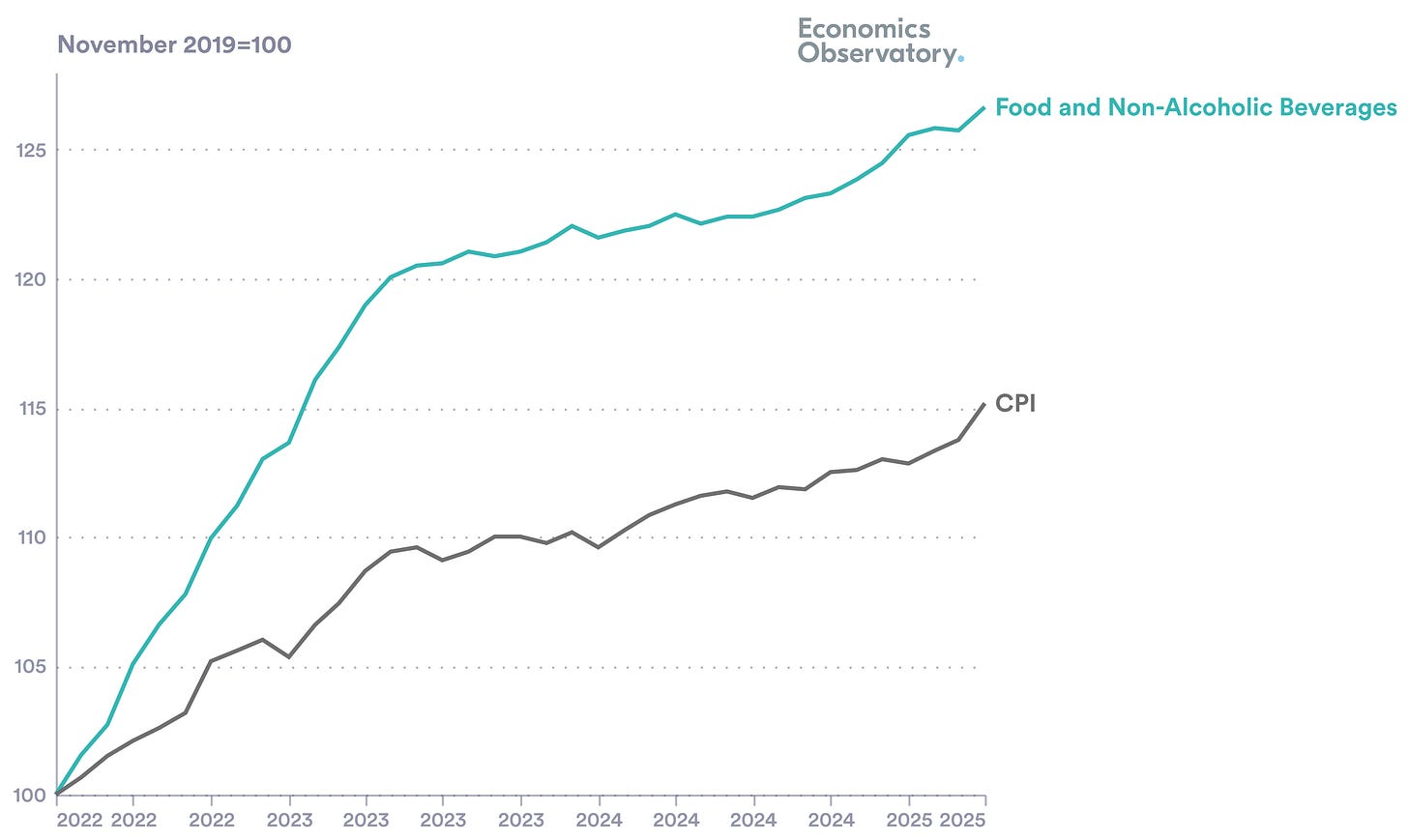

Underlying these big-ticket bills, everyday prices—especially food—are still rising more quickly than the Bank of England’s target. Comparing a consumer basket just containing food with the full consumer price index shows just how pricy food has become (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Food verses CPI basket of goods

Source: ONS

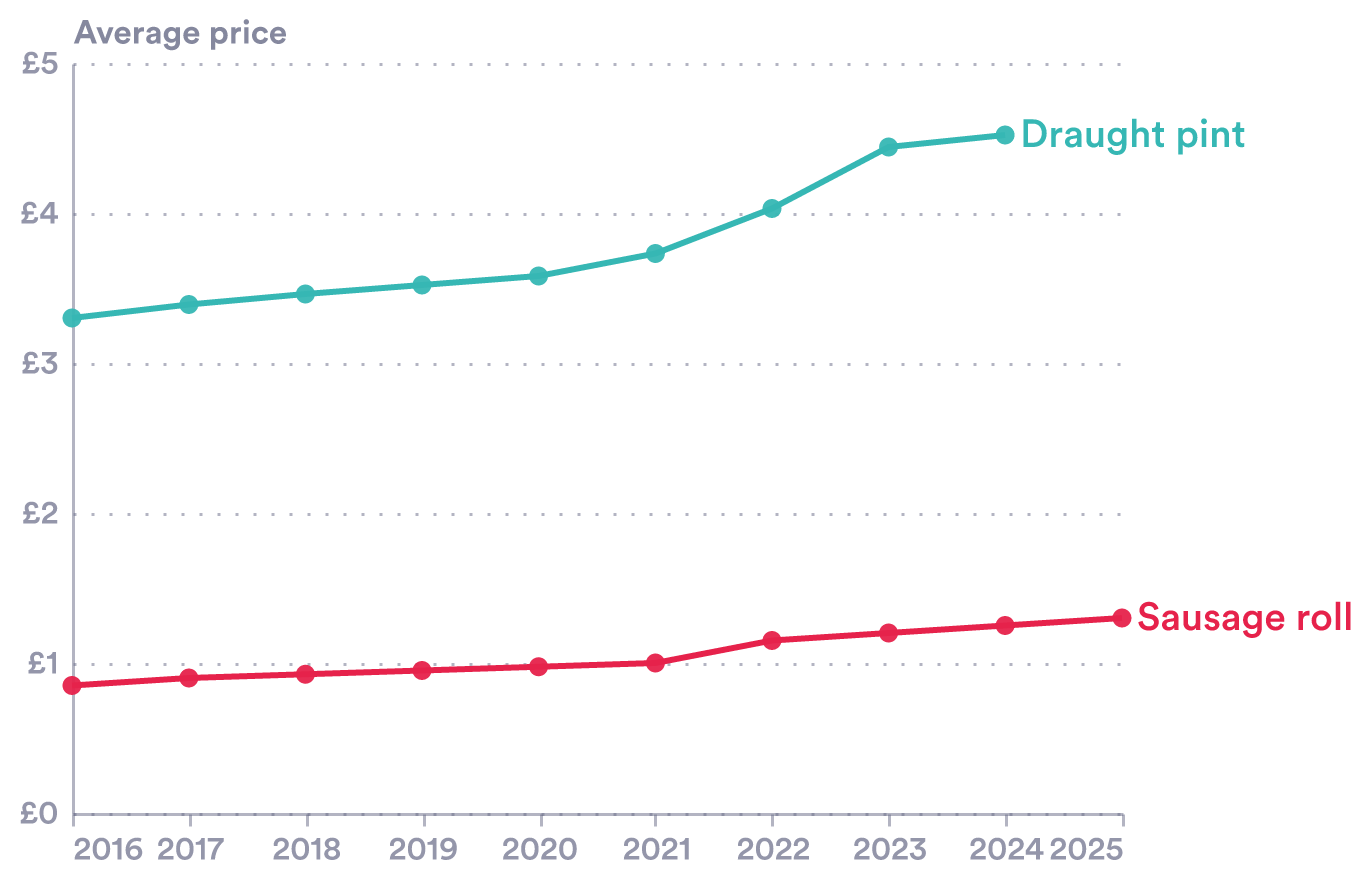

To get an insight into pricier food and drink, we tracked a couple of classics. The Greggs sausage roll—of which a reported 7 million are sold a week—has crept up. Just 85p back in 2016, a roll will now set you back £1.30 (on average). Pints too, are pricier: on average, a beer will now cost you £4.52. The days of the £2 pint, once a benchmark, are long gone.

Chart 2: The rising price of a pastry and a pint

Source: ONS, Statista

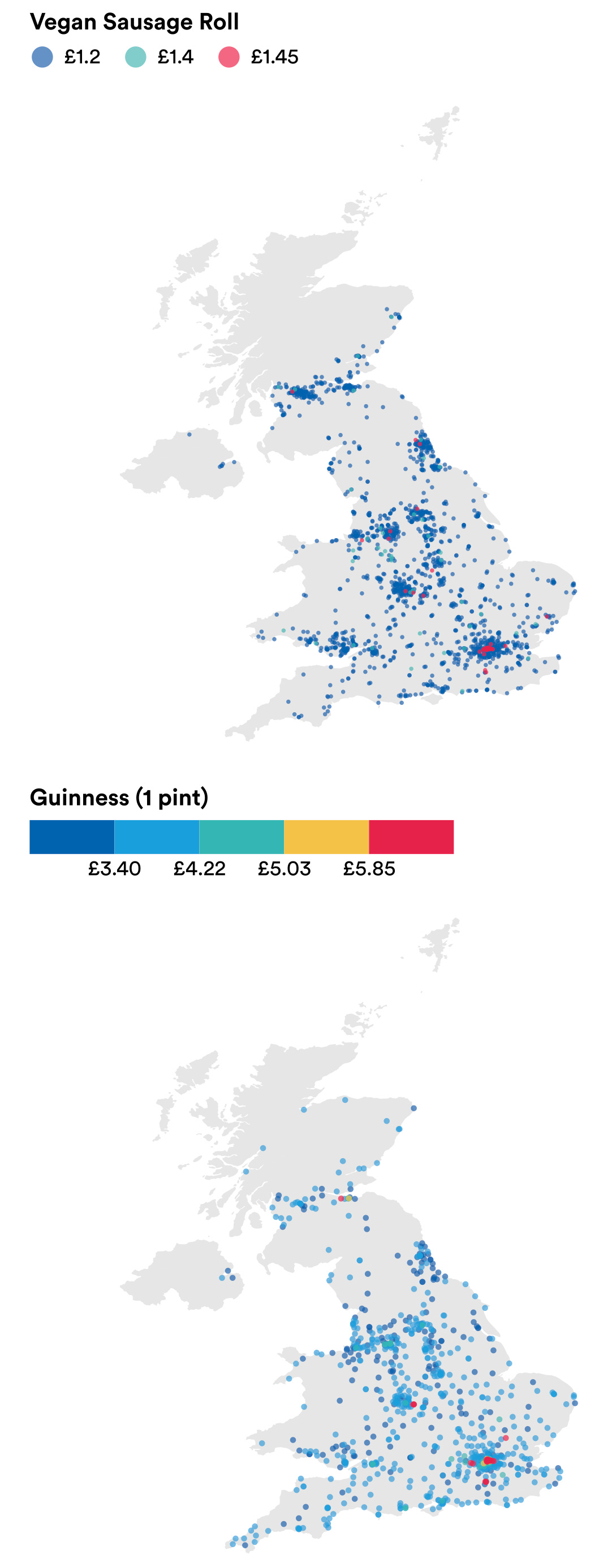

How much you pay depends on where you are. The dark stuff sheds some light on this. Using Guinness prices collected from Wetherspoons menus shows that a pint ranges from £2.59 in Peterlee (County Durham) and Batley (West Yorkshire) up to £6.66 at the Moon Under Water, a pub in Westminster.

Strip out airports (where high prices skew the numbers) and the 20 most expensive pints are all in London. Wetherspoons pubs are known for a no-frills, cost-cutting, approach—still, they charge a lot more when doing business in the capital.

Chart 3: Regional pricing: sausage rolls and pints of Guinness.

Source: Author’s illustration using Wetherspoons and Greggs data

Another example is Greggs’ vegan sausage roll – which stormed social media when it was launched in 2019. Its prices range from £1.20 to up to £1.45, a 20% rise. Venture into central London and the cost of veganism rises.

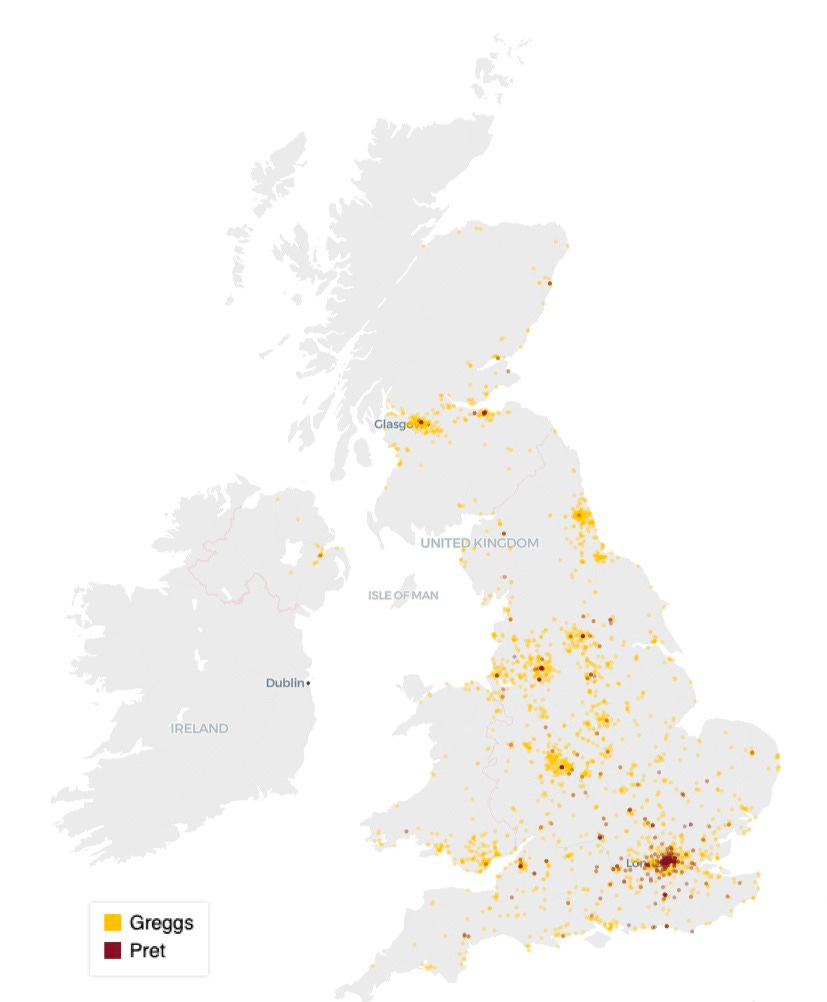

Pint and pastry prices are not the only regional difference. Researchers at Sheffield Hallam University have divided the country according to its café chains. Doing so reveals a ‘Greggs Britain’ and a ‘Pret Britain’ (see Chart 3).

Chart 3: Greggs vs Pret Britain

Notes: Every Pret A Manger and Greggs location in the UK.

Source: Author’s illustration with Pret and Greggs data

Pret A Manger operates around 475 stores across the UK. Over half (271) of the chain’s branches are in London—there is roughly one Pret per square mile. No other city comes close. Manchester has 14 and Edinburgh and Birmingham have just ten each. Outside metropolitan areas, Pret vanishes.

Greggs, by contrast, is everywhere. With over 2,500 locations, it spans high streets, retail parks and petrol stations. The chain, founded in 1939 in Tyneside, has its deepest roots in the North East but it has spread widely over the years. It recently completed its geographical conquest, reaching Cornwall with four new stores (although it still won’t sell a pasty there, to avoid clashes with the beloved regional speciality).

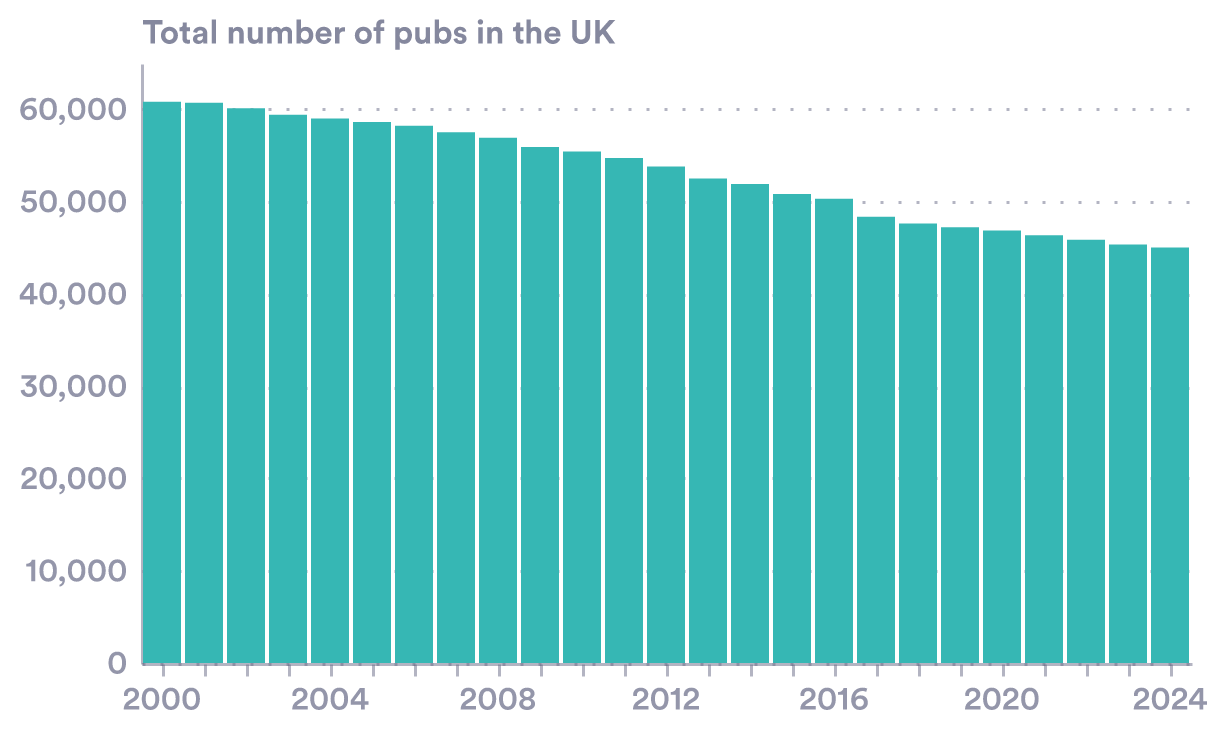

Higher baked goods prices are not sapping demand: both chains are expanding and opening new locations. The pub story is different. While around 21 new coffee shops pop up every week, a similar number of pubs are shutting their doors. Research suggests that by 2030, cafes and coffee shops will outnumber pubs on Britain’s high streets.

Chart 4: Where have all the pubs gone?

Source: BBPA

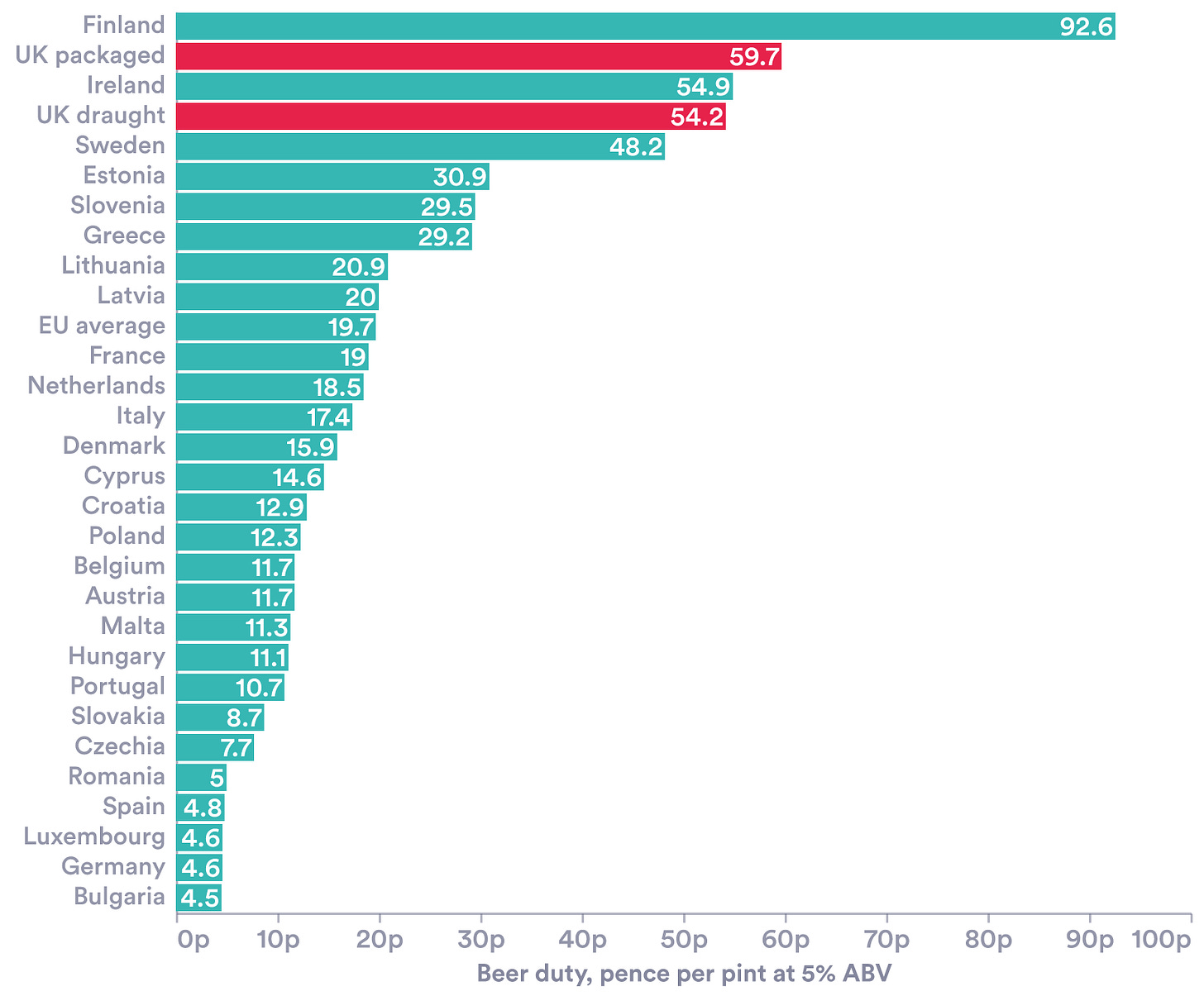

Cafés seem to be beating pubs for a few reasons. Tax is one. As our previous newsletter set out how rises in NI and minimum wages can drive up staff costs, really biting in lower-wage labour-intensive sectors, like hospitality. Pubs and breweries are amongst the most heavily taxed businesses in the UK. In comparison to Europe, the UK’s beer duty rate is one of the highest (see Chart 5). So pressures are higher for pint sellers than those offering pasties.

Chart 5: UK beer duty one of highest in Europe

Source: BBPA

Don’t just blame Westminster for high pint prices and our lack of pubs though—our own habits have shifted. Remote working is playing a role: cafés are favoured places to tinker on laptops. When we do drink, doing it at home is more likely. Over 65% of all alcohol in the UK is now sold through shops and supermarkets rather than pubs or restaurants. And an increasing number won’t touch a drop: sobriety is on the rise: around 20% of the British adult population don’t drink, up from 17% in 2011. Amongst Gen-Z the figure rises to 39%, up from 27% in 2013. A pastry and a pint is a cracking combination—one that on British high-streets is becoming harder to find.