This week’s note is a primer on public debt. Things look ominous. On Sunday I set out some thoughts in the Observer:

A 45-year view of bond markets

The article discusses how vital debt is. One reason is infrastructure (The Observer team found a nice picture of the construction of London’s sewers, which was debt funded). Another is that bond markets are a form of insurance against bad times.

“As well as helping to build the economy of tomorrow, bond markets protect us today by acting as a form of insurance. We don’t know what the crises will be on the road to 2070, but on a 45-year view we can be sure that many will come. Some will require a sudden issuance of debt. By stretching bond markets to the limit, advanced nations are eroding this buffer and making the future more fragile.”

Given the global nature of the problem, I think a global solution, probably involving the IMF, is going to be needed.

If that’s right, we are all going to need to sharpen up on debt. So here’s a data-driven explainer from the Economics Observatory team.

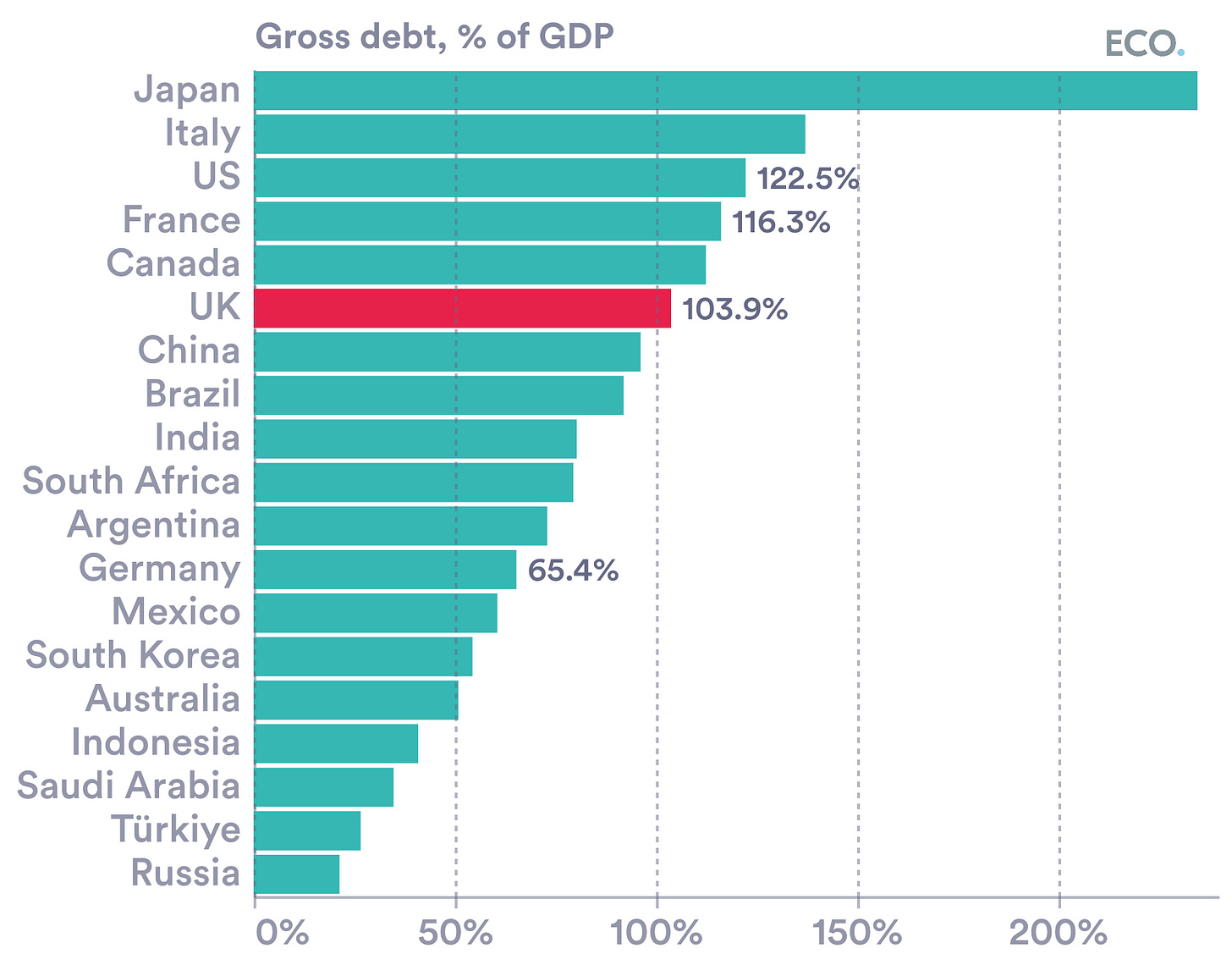

(1) How much debt is there?

Britain currently has £3 trillion of debt. This is 104% of GDP. Compared to the world’s top 21 countries by population this puts us 3rd on the list behind the US and Japan. Within the G20 group, the UK sits 6th. Other notable debtors include France (116%) and Italy (137%).

The government’s debt takes the form of bonds—IOUs which promise to return a regular payment over a pre-set period of time. These IOUs are sold to investors at auctions which are held most weeks. The government’s Debt Management Office provides data on the auctions, and the bonds that have been issued. The DMO reports that there are 101 types of bonds in issue, broken down as:

Medium and long term. 42 bonds, £1.2 trillion value, 43% of the total.

Short and ultra-short term. 24 bonds, £0.9 trillion value, 32% of the total.

Index linked. 35 bonds, £0.7 trillion value, 25% of the total.

Green bonds. Two bonds, £70 billion. Proceeds destined for low-emission transport, energy and decarbonisation projects.

Two of the long-term bonds last until the 2070s. So, Britain’s debt has a 45-year horizon. Since 1997, the UK has seen eleven chancellors. At this rate of churn the 2070 bonds will be paid back in 18 chancellors time. We need a long run view, in other words.

Chart 1. Debt outstanding

Notes: General government gross debt, G20 economies.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, April 2025.

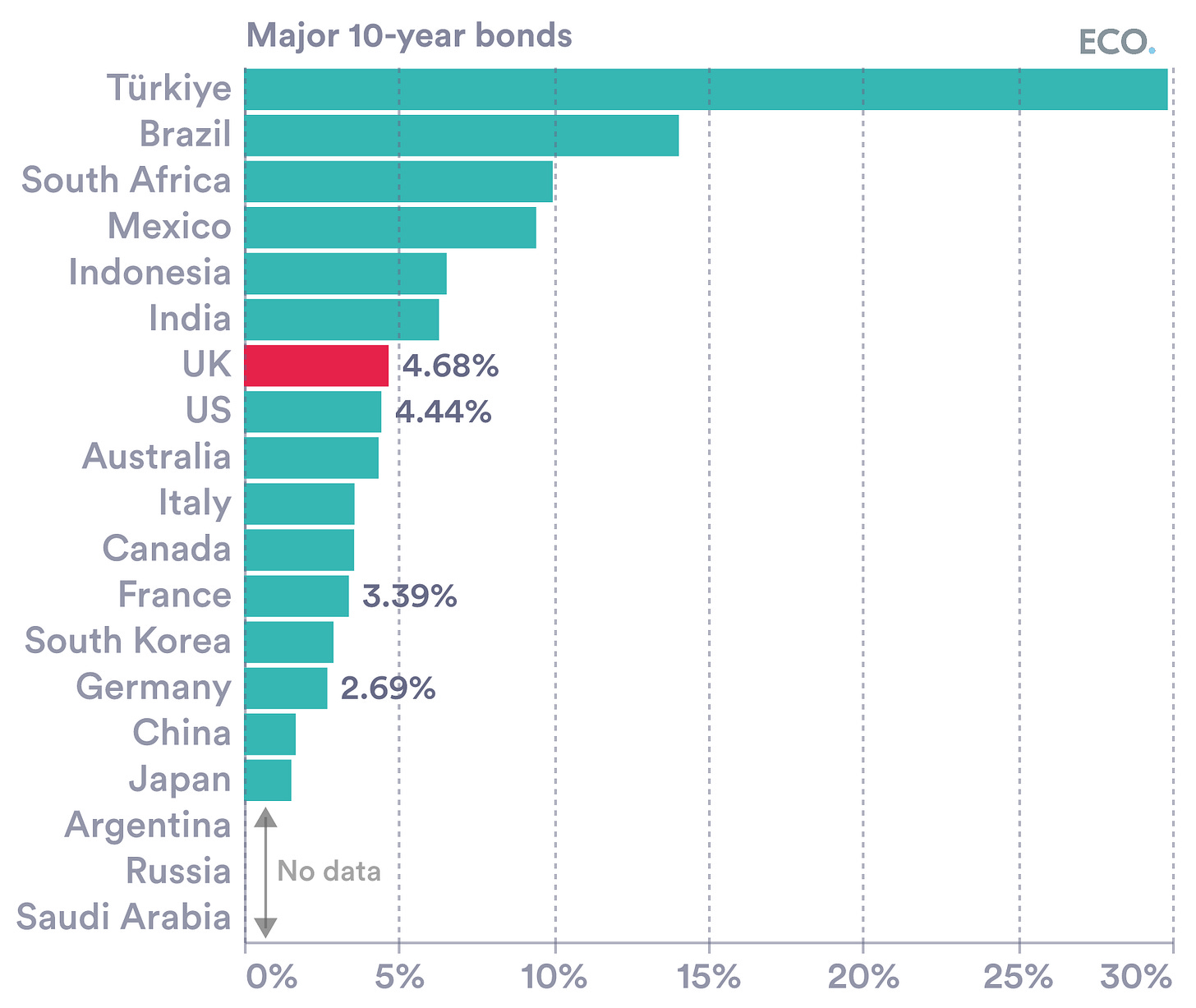

(2) How much do we pay?

The bedrock of government debt markets is the 10-year bond. At present, the yield on this debt is 4.7%—slightly higher than G7 comparators. The OBR expects interest costs to be £112 billion in 2025-26, or around 4% of GDP. This compared to 3% in the US, 2% in France and 1% in Germany.

In other words, debt is a major element of UK expenditure. Roughly the same as the education budget (£113 billion), twice the defence budget (£57 billion), fully seven times environmental protection spending (£15.9 billion).

Chart 2. Current bond yields

Notes: G20 economies, 10-year bonds.

Source: LSEG Workspace, accessed 18th July 2025.

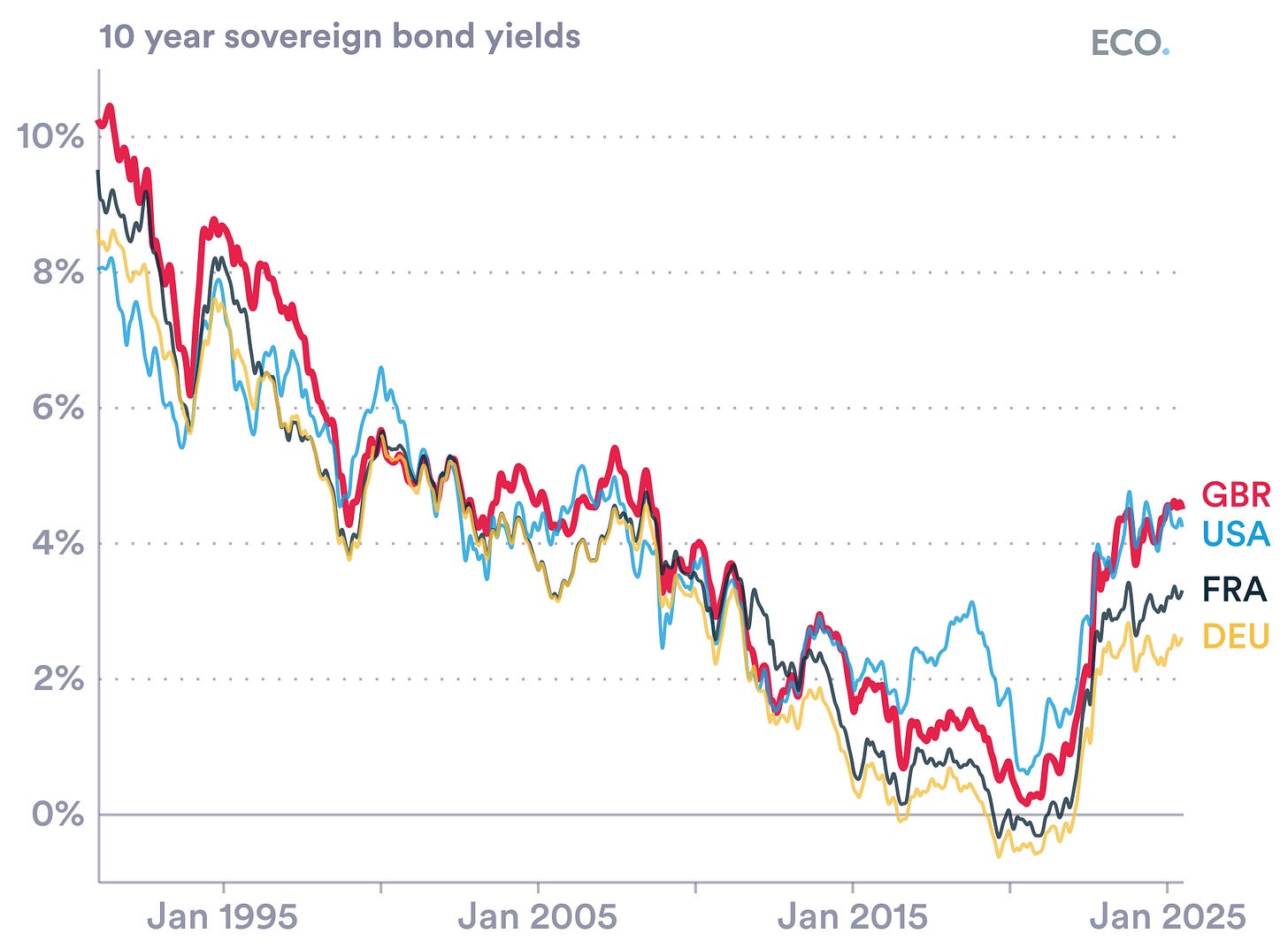

(3) How have bond yields changed?

The scale of G7 countries’ debts makes them sensitive to interest rates. For more than 30 years the story here was for a steady decline in interest rates (Chart 3, below).

Chart 3. Long-run yields

Notes: Major 10-year bonds, 31st January 1991 to 30th June 2025.

Source: LSEG Workspace.

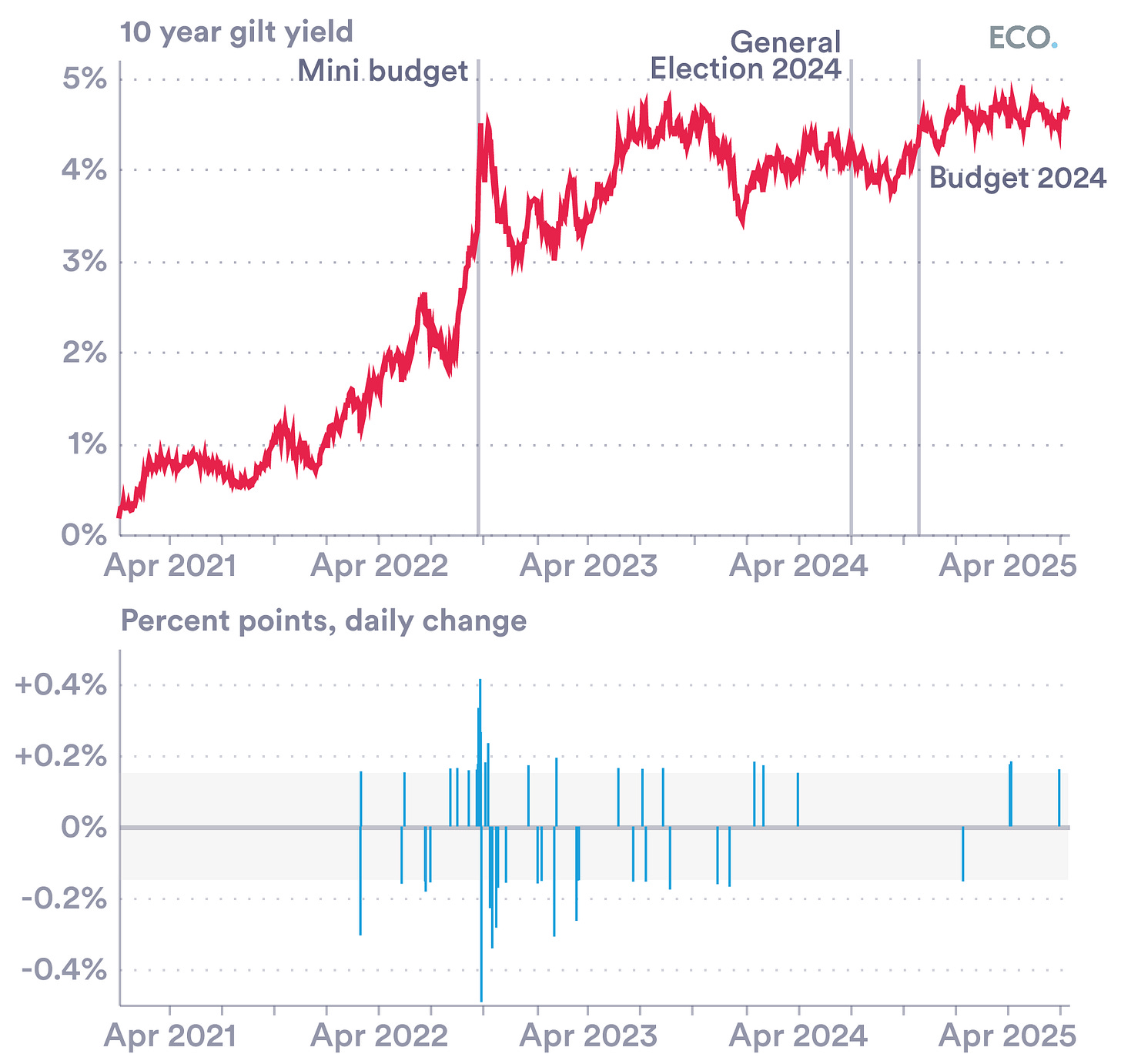

More recently there have been sharp increases—and volatility—in the interest rate on UK government bonds.

Chart 4. UK yields, recent data

Notes: Bottom chart excludes daily changes lower than 15 basis points (0.15%).

Source: LSEG Workspace.

It is simplistic (and dangerous) to blame all this on Westminster institutions. There are clearly bigger forces at work. For one thing, look again at Chart 3, above—countries track one another. And the inability to control debt has become a global trait too. Some examples:

Japan. There were poor results at bond auctions in May. Despite its debt burden, its debt has long been unusually cheap. Japan has been ‘defying gravity’, thanks to a carefully managed bond market. Could that be coming to an end?

US. The bond market played a big role in the rapid relaxation of “Liberation Day” tariffs. Whatever you make of Elon Musk, he has been successful in business. His DOGE programme set out to save $2 trillion. In April, BBC Verify found evidence for just 1.6% of that ($32.5 billion).

France. The minority government is paying more than EU peers to borrow. Past attempts to address the deficit led to the gilets jaunes mass protests – first sparked by increases in fuel taxes, then again in response to pension reforms. More recently, there has been a movement encouraging French workers to turn up late, to claw back the extra working time required by increases in the general retirement age.

Germany. Famously the most fiscally conservative nation in Europe is easing its budget rules. The changes mean spending on defence above 1% of GDP are outside the scope of Germany’s ‘debt brake’ rules, and the Lander are now permitted new borrowing of up to 0.35% of GDP annually.

(4) How does this impact the rest of us?

Government interest rates matter in lots of ways. They determine how much can be spent on public services. They influence firms, acting as a baseline for what large UK companies will pay on corporate bonds. Through this channel, high sovereign rates can kill off investment, act as a productivity drag, and erode real wages growth.

Perhaps most directly, they influence how much the rest of us pay on our own debts. (UK household debt is around £2.2 trillion.) Britons were hit by rate spikes on both credit cards and mortgages after the bond market rejected the 2022 budget. Now take an optimistic view: suppose you could calm the market and lower yields by 1 percentage point—that would save British households £22 billion a year, equivalent to the budget of the Home Office. ●

Chart 5. UK interest rates

Source: Bank of England. Notes: 1991 to 30th June 2025.

REFERENCES

Photo: HM Treasury, the UK’s Finance Ministry. Credit: Carlos Delgado; CC-BY-SA.

Debt

Office for National Statistics. General government consolidated gross debt (Maastricht). Public sector finances, May 2025. (Series ID BKPX).

Note: Gross debt is defined by the IMF as “all liabilities that require future payment of interest and/or principal by the debtor to the creditor”. The Net Debt measure sits slightly lower at £2.87tn, or 96.4% of GDP.

International Monetary Fund. Gross debt position. Fiscal Monitor, April 2025. (Series ID G_XWDG_G01_GDP_PT)

Debt Management Office. Gilts in issue. https://www.dmo.gov.uk/data/gilt-market/gilts-in-issue/

UK households’ liabilities. (Includes non-profit institutions serving households.) https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/timeseries/nnre/ukea

Islamic debt products. Gov.UK

Interest

Bank of England. Mortgages: Monthly revert-to-rate mortgages to households. (Series ID IUMTLMV)

Bank of England. Credit cards: Monthly representative credit card lending rate to households. (Series ID IUMCCTL)

The UK in 2068

Population projections. UN Population Division data portal.

Fiscal risks and sustainability. OBR.

The one thing which is missing from your excellent analysis of givernment debt is "who holds the debt". In the UK my understanding is that 75% is held internally. This does not pose a problem as it simply redistributes income between UK households. If this redistribution is a problem, eg when yields rise and bondholders receive a "windfall" gain, then the tax system can restore equilibrium. I admit that the external bondholders do raise a problem.

"It is simplistic (and dangerous) to blame all this on Westminster institutions. There are clearly bigger forces at work. " That's a relief. Here I was thinking they soiled their underpants while autoerotic asphyxiating themselves by taking on 25% of debt in linkers to fund fantasy liberal clown world. I also thought it was due to them also taking away their ability to control the inflation driving up these linkers because $713 billion of bonds were converted into floating reserves with QE, thereby putting them on the hook for interest payments at bank rate. Instead all of this is due to "wooo...forces or something man." Great news.