Rebuilding Britain: ten tips

If in doubt, just copy Lille.

Flags of Bilbao (Basque Country), Dortmund (Germany), Wyoming (US), Andalusia (Spain), Lille (France), and Duisburg (Germany)

Britain’s regional disparities are large. Last week we reviewed the data, pointing out the huge gaps in pay, job opportunities, and productivity between places. We also noted the looming spectre of local debt in local areas where the birth rate has dropped. You can find lots of interactive maps that track these metrics, and others, on our main site.

This week we look overseas for ideas. From Andalusia to Wyoming there are interesting case studies of how local governments have fought back against economic decline. What can the UK learn from these places? Here are 10 ideas:

(1) Economic osmosis doesn’t work.

The first step is acceptance. Just because your country has a Paris, Tokyo or London does not mean everything is going to be fine. There is a tendency in economics to be attracted by the idea of diffusion—that the rising tide of a megacity will lift all others. In the US, Wyoming is jammed between a bunch strongly performing states yet does badly. Spain, something of a star economically in recent years, has seen science bloom in Granada, Málaga and Seville—yet Andalusia is stuck. These cases and others show that each city or region needs an economic story of its own.

(2) Use data to find low-hanging fruit.

The more optimistic part of the story is the fact that international experience tells us, in part, what to do. We know that regions tend to perform better when their economic offerings are more “complex”—i.e. they create more sophisticated goods and services (steel production is more complex than coal mining, for example). The complexity of an economy can be measured by tracking inputs, processes, skills and so on. This means directed investment can be used to build on a place’s strengths and fill its gaps.

Andalusia is an example here. Researchers at Harvard University’s Growth Lab recently analysed export data to assess the current economic capabilities of Andalusia. This pinpointed products and industries— they found fully 130 options—which, if improved, could help the region grow in a sustainable way. Clear gaps in the regions included chemicals and metals. This data-driven approach to policy advice has the potential to boost economies.

(3) Creating jobs is better than sending money.

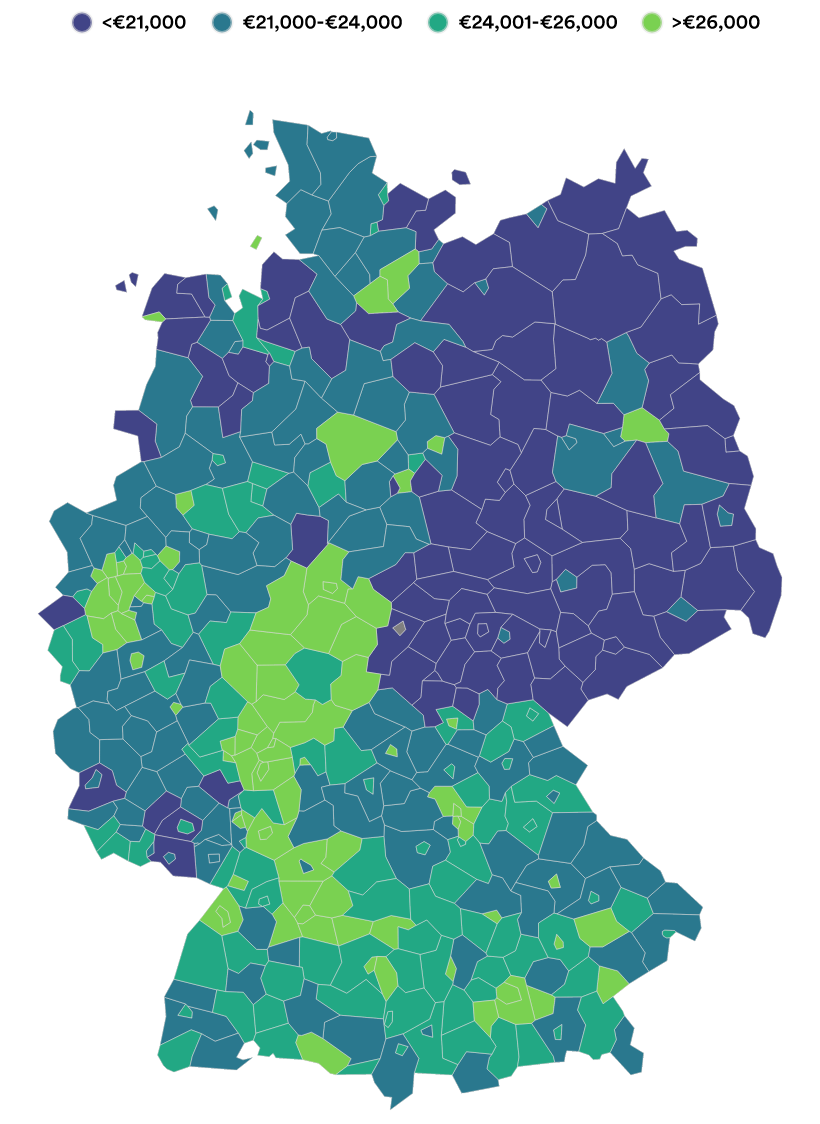

Case studies show that progress comes from job creation: transfers of funds to lagging regions alone may not be enough. Germany’s reunification is an example. Here’s a map of pay in 2000.

Map 1: Wages in Germany, 2000

Notes: Gross wages per employee by district. Source: German Federal and State statistics portal

There have been €2 trillion in transfers from West to East over 30 years. The money improved infrastructure on transport networks and public spaces, and services such as schools and local administration, but without tackling gaps in productivity and pay, East Germany’s economy drifted toward low-growth sectors. Yet the West-East divide is still pretty clear on economic maps (Map 2).

Map 2: Wages in Germany, 2022

Notes: Gross wages per employee by district. Source: German Federal and State statistics portal

Bilbao is a city to mimic. Once heavily reliant on heavy industries, it successfully reinvented itself, becoming one of the most prosperous places in Spain. For over four decades, the Basque government has aimed to foster knowledge-intensive sectors. This involved promoting R&D within firms (in part by providing funding, and retraining staff) as well as establishing not-for-profit technology hubs that facilitate knowledge transfer. Today, Bilbao has knowledge-intensive clusters, including aeronautics, as its economic drivers.

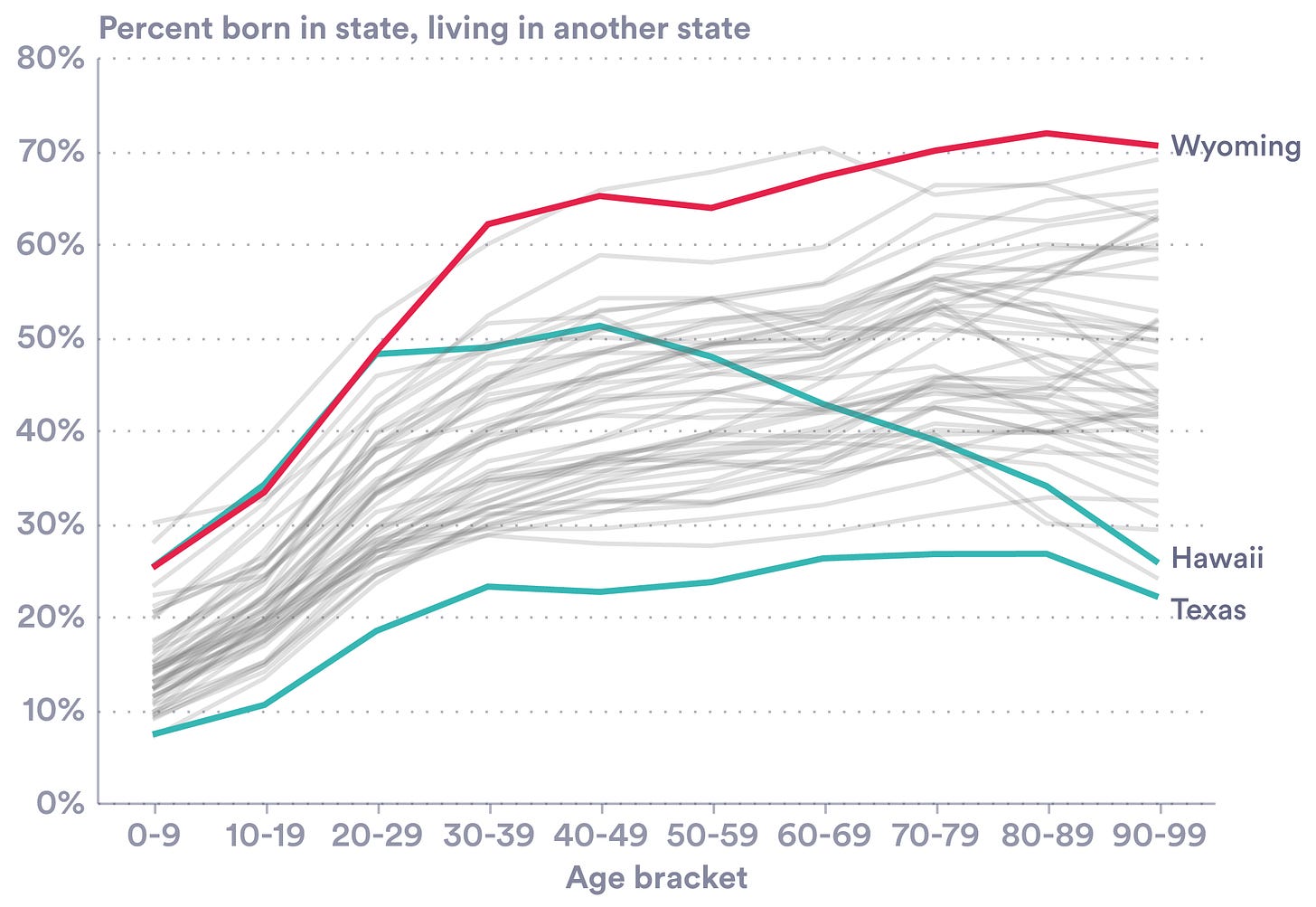

(4) Brain drain matters—compete for minds.

Wyoming vividly illustrates the cost of brain drain. Despite investing more per capita in education than any other state, Wyoming is losing its young population at an alarming rate. By their late thirties, nearly two-thirds of people born in Wyoming have moved to other states—the highest outmigration rate in the US. Interestingly, these young people aren’t all heading to major coastal cities like New York or Los Angeles; instead, they tend to relocate to nearby states offering better amenities—especially cultural activities and restaurants.

Graph 1: Wyoming outmigration

Source: Growth Lab, 2024

Dortmund is a place that has reversed this kind of decline. There the local government, working with private sector, transformed the city into a hub for arts and creative industries. This included cultural infrastructure—a new art centre and concert hall—as well as urban developments and a technology centre on the site of a former steel plant. All this generated new service industry jobs, making it attractive to young families. In Bilbao a similar development package, and similar success, can be seen.

(5) It is all about housing, everywhere.

It can sometimes seem that Britain is obsessed by housing and planning reform. The government is targeting 1.5 million new homes over five years, with councils mandated to meet the target of 370,000 homes a year. This is far above the current rate (Graph 2). But the UK is just one example of a global problem. Wyoming’s exodus is driven by unaffordable housing and poor amenities—both blocked by regulations that tend to penalise dense housebuilding.

Graph 2: Housing completions by year, UK

Source: ONS, 2025

The UK could look to Lille. The French city’s strategy, adopted in the 1990s, focused on making the city more attractive to residents and more competitive economically by creating a denser inner city and limiting further outward expansion. Traditionally dominated by single-family homes from its industrial past, Lille set a goal to build two-thirds of new housing within existing city limits, with minimum density requirements. Central brownfield were converted to mixed-use areas, including housing. Today, Lille ranks as France's third-largest service hub, and has a significant financial sector. It has also developed strong clusters in mail-order and large-scale retail, supported by auxiliary industries like logistics, graphics, and advertising.

(6) Transport, transport, transport. Better transport can soothe both a brain drain and a housing shortage: if your trains are bullet-fast, people can just commute in. Here the UK lags: in major European cities, 67% of residents can reach the city centre by public transport within half an hour—in Britain, only 40%. All large British cities (Glasgow is an exception) have worse transport than their comparable European peers. Trams have become a norm overseas. Instead, Birmingham, Bristol and Leeds rely on buses and are clogged up by cars.

Graph 3: People who can reach the centre in 30 minutes (% of total residents)

Source: Centre for Cities, 2021

For solutions look, again, at Lille. The city capitalised on its improved position between Brussels, London, and Paris after connecting to the TGV (1993) and Eurostar (1994). Transport has remained core to its development policies. The Armentières area, a former industrial zone, became a hub with both commercial and residential spaces supported by a covered bus interchange, a park-and-ride scheme, and dedicated bus and bike lanes. Integrated ticketing for trains, buses, and bike shares made travel easier. As a result, daily passengers grew from 3,300 in 2005 to over 5,000 in 2012. Better transport helped the city thrive.

(7) Infrastructure is not enough.

Firms need a favourable environment to flourish—this includes to finance, skilled workers, infrastructure, and clear regulation. Yet, many local development strategies emphasise a single element. Duisburg, Germany, is an example. In some areas, including logistics, the city adopted a package—infrastructure, skills training, international promotion, and start-up assistance—and things went well. Where they focused on just one element (often infrastructure) the improvements were scant.

(8) Pick (local) winners.

For the past 50 years or so, the notion of the state “picking winners” has been a poisonous one for economists. The argument has been that the state is poor at identifying the best firms, and that cronyism and lobbying end up meaning money is wasted when targeted industrial strategies are attempted. Yet a body of evidence and experience shows that having a regional champion does help. This is because ideas—in particular R&D—can spill-over within a city or region. (Alfred Marshall spotted this in the late 1800s, saying that ideas were “in the air”—helping all firms in a city).

This suggests some directed investment could be sensible. Andalusia is an example here. Its location, abundant solar and wind energy, and access to critical minerals give it a natural advantage in sustainable power generation. As our colleagues at Harvard show targeted investments could turn it into a low-carbon energy hub.

(9) Devolve more power.

Local leadership has been central for the turnarounds in these case studies. France recently hit 40 years since a major decentralization push (the 1982 ‘Gaston Defferre’ laws) which gave its regions authority and resources. Lille’s redevelopment benefited greatly—today the Lille Metropolitan Authority generates 78% of its own budget. This means it has significant fiscal independence and decision-making power without relying on government grants for transport or development projects. In Germany cities like Dortmund and Duisburg benefit from one of the most decentralised fiscal systems in Europe, with roughly half of government expenditures managed at the regional Länder or municipality level. This setup allows for close coordination between city and regional governments with spending power held locally. By contrast UK regional and local government have relatively little power to make their own investments. (Graph 4).

Graph 4: Local government investment as % of GDP

Source: OECD, 2022

(10) Find money to support all this.

This most obvious lesson is the hardest to get right. Yesterday’s Spending Review showed just how tight Britain’s coffers are. On top of that we explained last week how many local authorities have declining populations and growing debts. Still, a step change will be needed. In the last 40 years in the UK, expenditure on regional economic development never surpassed 0.2 % of GDP, with 0.1% the norm. In contrast, Germany routinely spends four to five times as much overall, and if we focus specifically on policies for enhancing weaker regions, Germany spends something of the order of 25-30 times more than the UK. Look out for a newsletter on where to find these funds later this year…

As ever, references are below. Please do share the newsletter if you are enjoying it.

REFERENCES

Articles

Economics Observatory. German Reunification

Economics Observatory. Shrinking Wyoming

Economics Observatory. Spain’s poorest region, Andalusia

Reports and publications

LSE/Resolution Foundation. Lessons from successful ‘turnaround’ cities for the UK

LSE/Resolution Foundation. German Reunification

LSE/ Resolution Foundation. Building blocks

Centre for Cities. Measuring up: Comparing public transport in the UK and Europe’s biggest cities

Centre for Cities: Accelerating net zero delivery: What can UK cities learn from around the world?

Growth Lab. How Wyoming’s exodus of young adults hold back economic diversification

Government Outcomes Lab. Turnaround Cities: Western Europe Case Studies – Insights from Lille, France and the Basque Country & Bilbao, Spain

Government Outcomes Lab. Turnaround Cities: German Case Studies – Insights from Dortmund, Duisburg and Leipzig

NIESR. The Fiscal Implications of ‘Levelling Up’ and UK Government Devolution

Wendell Cox. Dermographia International Housing Affordability 2024

Data

Economics Observatory. Data Hub

These ten economic tips for Britain miss the mark. The UK can't just copy the French city of Lille which is blessed by its location in the heart of Europe. Nor is there an easy path to emulate Germany. Most regions in Germany have for decades enjoyed greater wealth than the UK (London excluded). The reason for this is simple: Germany has a century-long legacy in advanced manufacturing. Why did Dortmund turn around after it could no longer rely on coal? Because they build a concert house to lure in families as the article suggests? No: serious companies make the difference. A quick Google search reveals that "Dortmund has become a leader in micro and nanotechnologies, as well as a significant logistics hub. Other important sectors include research and development, IT, medical science, and robotics." These pay the taxes that fund the concert hall. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to replicate this success. You can't just say to your local economy: Build more complex products per your point 1. Nor can you trust the municipal government to pick winners per your point 8. Per a personal anecdote shared with me yesterday from Germany, picking winners literally means buying expensive machines today when there are subsidies, so that these machines can be used in two years once the factory has been built. Mind-boggling if you consider how for-profit airplane manufacturers treat their most expensive input--engines. Basic economics comes to the rescue. Businesses flourish if given access to cheap inputs and human capital. Britain could easily bring electricity cost down in the medium term by replacing its aging fleet of nuclear power plants. And Britain could improve the human capital of workers by offering better technical training. South Korea copied the German model of skill-based education. There is no reason other countries couldn't do the same. Regarding your point on local versus national investment. Isn't that, for the most part, just accounting? In some countries the municipality does X. In others, it's the state or national government that does X. I'd note that the Netherlands, Europe's most successful large economy, equally finds itself below the EU average. So why problematize? Many divisions of political authority can work. When making the comparison to France, the reason that French municipalities get so much done is because municipal leaders are very powerful per the constitution. Until recently (when Macron's legislation prohibited this), the most successful French mayors often enjoyed a dual mandate where they served as members of parliament in addition to serving at the municipal level. Now, surely, if you enhance executive power, good leaders can get more done. But this whole French model (which can work just fine tbc) is anathema to British politics where individuals tend to hold less power and control by legislators is stronger. I'd say: why mess with the constitution when the basic problems are the cost of energy, housing shortages and too low human capital? I'd say to the UK government: Bet big on nuclear, improve non-university skill-based training in lockstep with the private sector and maybe meddle a bit less with planning so that developers can focus on building houses that people would wish to live in rather than being in compliance with regulation. On that last point, a bit of a personal quirk: I for one do not understand this obsession with density: Most people I know prefer a terraced house over a skyscraper, green suburbs of human proportion over living in the Barbican. Those might be a minority. But why not let the market (via developers who seek to maximise profit) decide which model best serves individual tastes? Assign more land to suburbia, and see if people would like to move there. For that purpose, four numbers---maximum height, number of units, total square metres and minimum number of square metres per unit---is all that a developer needs to know to get going and that gives politicians enough scope to mitigate the externalities.

Well written and interesting! From the experience of America (which may not apply there), those that actualized and in large part designed our pre ww2 system believed that the behaviors of all level of governments and other elements of the system, are mostly determined by the broader system architecture itself. From roughly the 1830s onward until pre post-ww2 era, when the USA operated under a very different system architecture., the US developed a decentralized framework in which local governments, while sometimes flawed, were key parts of broader economic and institutional designs that gave them quite meaningful tools and incentives to promote real, grounded growth. They were strong economic, fiscal, academic, and scientific actors with real powers there, this was coordinated democratically with very strong national interlinkages between local party structures of parties that were decentralized and publicly accessible mass-member parties, well, it would take longer to explain, but that system ran America from roughly the 1830s until after ww2 and it was extremely productive